My first post was in 2010, a standard bitter in honor of close colleague and astounding scientist that passed. I was in my fourth year as a post-doc at Columbia University studying how retroviruses (HIV, MLV) interact with the cells they try to infect. Time was in abundance, allowing me to brew in a small Bronx apartment while I gathered many friends and scoured the city for rare-to-find craft beers. I was able to ranch yeast and create a bank, isolate unique Brettanomyces strains, and collaborate with a world renown master brewer. Most importantly, I learned as much as I could about the science behind brewing beer. My time in academic research came to an end, and I married the most amazing woman I have ever known and met another one:

Natalie, my beautiful daughter, was a game changer for me. I assume that most father’s sense of their place in the world changes dramatically when your first-born looks straight into your eyes. Job hunting was next, and I was lucky enough to find a great job doing process development for vaccines at Merck. Moving and settling in, enjoying fatherhood, and trying to secure my family’s future has made me feel slightly old.

As a result of all of this stuff, my last post was back in May. I began to re-read some of my old posts and realized that this blog has been is linked to so many wonderful memories, both beer and non-beer events that I can’t possibly ignore it anymore. It’s posts serves as markers for my past. It is this for this reason I intend to start posting again.

And an experiment may be the best way to start posting again. As a recap, I began brewing experiment beers for a yeast class that I taught at Brooklyn Homebrew. Ben and Danielle were kind enough to provide resources and space for my scientific curiosities that kept brewing. In contrast to my work life, my style of experiments are not rigorous and grounded in statistical significance. The goal has always been to pique the interest of the vast majority of non-scientific brewers, both professional and amateur. More importantly, I do not have the resources at home to measure key components of the brewing process. Instead, my conclusions rely on the most important data point – the beer drinker.

I am teaching again, this time at a great homebrew store in PA – Keystone Homebrew. Jason Harris, along with Lou (store manager) has been kind enough to provide support and space for the yeast class and the experiment beers. I’ve already taught two classes, and the most recent one was this past Saturday (November 9th).

Oxygen

Yeast are facultative anaerobes, meaning that they prefer to use oxygen to produce energy efficiently through oxidative phosphorylation. In the absence of oxygen, yeast still produce energy but with the inefficient process of alcoholic fermentation. Luckily for brewers, yeast will almost always undergo fermentation due to the Crabtree effect, where in the presence of excess sugars, even if there is oxygen, yeast will produce ethanol and CO2.

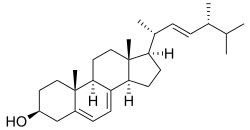

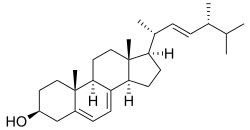

The main reason yeast need oxygen is for the production of unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) and sterols. Both molecules make up the plasma membrane of the yeast cell. I won’t go into how they are synthesized, but sterols, such as ergosterol pictured below, is present in the cell membrane at much lower concentrations. Sterols provides fluidity, making the membrane easier to bend and twist in shape.

Without sterols, UFAs would form rigid micelles, or droplets of fats. Importantly, this membrane fluidity allows for other vital proteins to be imbedded in the membrane. Some of these proteins are responsible for importing not only complex sugars (maltose, maltotriose), but vitamins, minerals, and cofactors. With poor cell membranes yeast will not tolerate increasing amounts of ethanol (which is why oxygenating that strong ale is crucial). Lastly, if the cell membrane is not healthy enough, bud scars from cell budding will take a toll on yeast health and restrict future growth.

What are the consequences of introducing too little or too much oxygen? It is best to think of it biochemically – that is, oxygen acts as an accelerant to certain biochemical pathways. For example, what I did not mention before is that O2 drives the synthesis of UFAs and sterols through a cofactor called Acetyl CoA.

What are the consequences of introducing too little or too much oxygen? It is best to think of it biochemically – that is, oxygen acts as an accelerant to certain biochemical pathways. For example, what I did not mention before is that O2 drives the synthesis of UFAs and sterols through a cofactor called Acetyl CoA.

I talk about this molecule a bit in my post on esters and it sits at the crux of critical yeast biochemistry. In this case, oxygen drives acetyl CoA to form lipids (UFAs, sterols). As more acetyl CoA is used to make UFAs, less is used to make esters and fusel alcohols. Therefore, beers that have more oxygen tend are cleaner in esters and fusels (think IPAs). Beers that have less oxygen will have more esters and fusels and are more fruity (think English ales). Increasing oxygen will grow more yeast cells as their membranes are super healthy and ready for budding. The increase in yeast biomass will add a bump in attenuation and may even thin out the beer since the yeast will be so active.

How much Oxygen?

Homebrewers have endless methods of adding oxygen such as shaking and splashing the wort, sloshing the wort from bucket to bucket, aeration with aquarium pump, and adding pure oxygen. I have heard lots questions since many homebrewers practice different techniques:

- How long do I shake?

- Should I use a drill with a whirl attachment?

- How long do you aerate with a pump?

- How long do you pump in pure O2? At what flow rate?

Let me answer all of these questions by saying that whatever works for your system that gives you the best beer is what you should do. Experimenting here is key. Brew that same pale ale three times, one with splashing, one with pure O2 (one minute), and one with pure O2 (five minutes).

In reality, as homebrewers it is very difficult not to introduce O2 once the wort is cooled. Simply transferring the cold wort into a carboy (without splashing) will add some amount of oxygen for the yeast to use, however this is far from ideal. Yeast need greater than 8 parts per million (ppm) to adequately ferment a batch of beer. Here are some numbers on different methods (keep in mind that O2 dissolves less in higher gravity wort) on an average batch of homebrew (5 gallons, 1.050 – 1.070):

- Shaking: 2 ppm

- Aquarium pump: maximum of 8 ppm

- 30 seconds pure O2: 5 ppm

- 60 seconds pure O2: 8-10 ppm

- 2 minutes pure O2: greater than 14 ppm

- The above pure O2 is assumed to be one liter per minute.

Splashing the wort is a very ineffective method of introducing oxygen and may even introduce contamination. Notice that with an aquarium pump, air can only give you a max of 8 ppm, whether you pump for five or thirty minutes. Oxygen makes up only 21% of dry air so there is only so much O2 you can force into beer with this method. Moreover, 30 minutes of aquarium pumping may drastically reduce head formation since you will create so much foam. The only way to get enough oxygen into your wort is by using pure oxygen with a sintered stone.

Exactly how much O2 to add to your beer as this depends on many factors:

- Yeast strain (different O2 requirements for different strains)

- Wort gravity (need more O2 for higher gravity worts)

- Beer style

Beer style and flavor profiles generated from oxygenation is the most important factor to me and is the basis of my experiment. For example, will adding less oxygen enhance fruity characters of some english ales? Would my IPAs be cleaner with higher amounts of O2? Would there be any changes in fusel alcohols? Would the body be thinner or fuller? Textbooks and the internet can tell you the answers, but I feel it is better to experiment and find out for yourself.

For the experiment beer, I brewed an ESB in a ten gallon batch at Keystone Homebrew (OG: 1.056 with 40 IBUs):

- 1 lbs Crystal Light – 45L (Thomas Fawcett)

- 1 lbs Crystal Malt – 90L (Thomas Fawcett)

- 8.0 oz Pale Chocolate Malt (Thomas Fawcett)

- 12 lbs DME Golden Light (Briess)

- 2.00 oz Target [11.00 %] – Boil 60.0 min

- 2.00 oz Goldings, East Kent [5.00 %] – Boil 0.0

- 1.0 pkg British Ale II (Wyeast Labs #1335)

From this wort I split the batch four ways and provided different amounts of oxygen:

- 30 seconds of splashing the carboy

- 45 seconds O2

- 5 minutes O2

- 10 mgs of Olive oil

Sample (1) represents what a new homebrewer might do. I did not dump the wort between two buckets but rather sloshed the wort around in the carboy. This sample should have little dissolved O2. Sample (2) is my default oxygenation regimen at home – I usually add pure O2 for 1-2 minutes in a 5 gallon batch. Sample (3) was to observe any changes in the other direction with large amounts of oxygen added to the beer. When I did oxygenate this batch, the foam generated was huge, almost a 3 gallon tick mark. Unfortunately I did not have access to a medical grade O2 regulator and was unable to determine flow rate. I opened my regulator, what you typically find at homebrew stores, to its max setting.

Sample (4) may be the most interesting of all. I decided to mimic what Grady Hull, brewmaster at New Belgium, did for his masters thesis at Heriot-Watt University. The thesis can be found here and is generously hosted by brewcrazy.com. In a nutshell, he added dissolved olive oil to the yeast starter of a commercial batch of Fat Tire as a source of linoleic acid, a precursor to UFA synthesis and did not aerate the wort. The reasoning being that the oil provides all the UFA and sterol needs of the cell and you don’t need to add O2. The goal of the experiment was to prolong beer half-life since oxygen has a severe staling effect. What they found was that the beer took a bit longer to ferment and was slightly more fruity. Independent tasters actually preferred this beer over the control beer.

Sample (4) may be the most interesting of all. I decided to mimic what Grady Hull, brewmaster at New Belgium, did for his masters thesis at Heriot-Watt University. The thesis can be found here and is generously hosted by brewcrazy.com. In a nutshell, he added dissolved olive oil to the yeast starter of a commercial batch of Fat Tire as a source of linoleic acid, a precursor to UFA synthesis and did not aerate the wort. The reasoning being that the oil provides all the UFA and sterol needs of the cell and you don’t need to add O2. The goal of the experiment was to prolong beer half-life since oxygen has a severe staling effect. What they found was that the beer took a bit longer to ferment and was slightly more fruity. Independent tasters actually preferred this beer over the control beer.

For my experiment I added olive oil directly into the wort (no starter were made for each sample). Importantly, the amount of olive oil I added followed close to what Gary Hull did (1 mg per 25 billion yeast cells), which was exceedingly small (about a tenth the size of a pinhead). Moreover, olive oil will not dissolve in wort and must first be dissolved in 100% ethanol. For any homebrewers reading this – do not add a drop of olive oil to your beer. I had to weigh 1 gram of oil, dissolve it, and make a serial dilution until I had close to 0.1 ug/ml. Of this solution, I added 100 uls directly to the wort.

The beer is already fermented, bottled and was sampled at a yeast class this past Saturday (11/9/2013) at Keystone Homebrew. Similar to my past experiments, I will post flavor profiles from the students as data points in a future post.

Cheers!

For both beers I asked Mr. Schaumloffel what his favorite craft beer is and he mentioned Brooklyn Brown ale. Although there is no recipe, I tried to clone the beer and found most of the ingredients – English and Belgian malts and hops along with some late American hops for flavor and aroma. Here is the recipe (6 gallons) which was split between Rene and Mr. Schaumloffel:

For both beers I asked Mr. Schaumloffel what his favorite craft beer is and he mentioned Brooklyn Brown ale. Although there is no recipe, I tried to clone the beer and found most of the ingredients – English and Belgian malts and hops along with some late American hops for flavor and aroma. Here is the recipe (6 gallons) which was split between Rene and Mr. Schaumloffel: